Science Distilled: March Preview

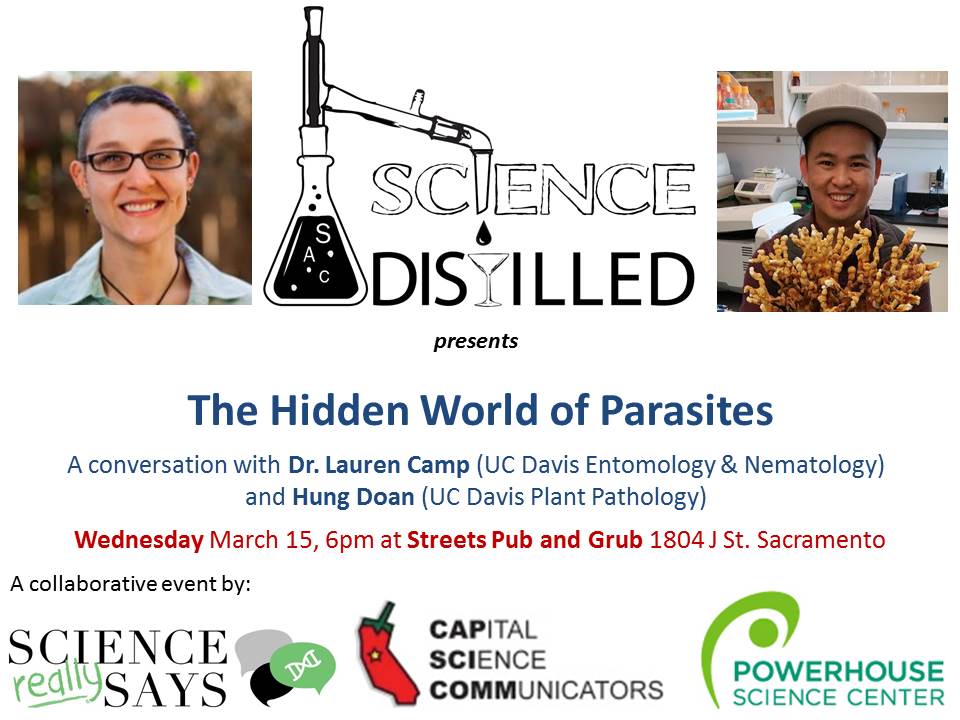

This past Wednesday, March 15 we heard from Dr. Lauren Camp of UC Davis Entomology & Nematology and Hung Doan of UC Davis Plant Pathology. They both spoke about parasite diversity, the many different hosts parasites attack, and the way parasites can hide. Here's a quick interview for you to meet the people behind the science!

What inspired you to study science?

Hung: Curiosity. As a child I was always curious about how things work. At first I wanted to study medicine, but it turned out I was afraid of blood, and didn't like harming rats for research. Plants don't get hurt so I realized I could enjoy research on plants.

Lauren: When I was a kid I realized it was something that I liked. It was also something that I was good at. I would look at my hair, fingers, and toys under a microscope. And my dad is a scientist. While it wasn't a path he pushed me toward, my siblings and I would go to the lab with him during the summers. I started with an interest in human research and medicine, then realized I didn't quite fit in with the premed crowd. I took an invertebrate biology class and was so excited by it. You look at animals and think they are all just fuzzy things with spines- but there is so much interesting variation in animals beyond that. And then I started to study parasites and I was done. They were so fascinating evolutionarily, in terms of what they can do and how common they are.

Do you have any affection for your study organism?

Lauren: It's hard to have affection for something that is harming people and animals, and plants that we depend on for food. My study organism is a parasite that does relatively little to hurt raccoons, but can get into the brains of humans. I do find them fascinating though. A parasitologist once told me, saying you like parasites is kind of inappropriate, because they are harming people all over the world. I do experience excitement when talking to other people about it.

Hung: The pathogens I study just harm plants. Whether I see it in the field or in the lab, I get excited when I recognize the diseases. During my masters' degree I worked with a plant disease called Fusarium, which lives in the soil indefinitely. When a farmer tells you they spotted it in the field, it's exciting. Because you can then breed resistance to the disease, and the crops can overcome the disease. I definitely have pictures of Fusarium around – it's kind of my research baby.

When someone approaches you as a scientific expert, how do you react?

Hung: When you speak with people who don't have training in science, so many things can surprise them. Just the idea that plants can get disease can be surprising. I grew up in San Jose, where there is lots of biotech, but a disconnect in the way people don't really know where their food comes from. Plenty of people I know studied a little biology in school, but sort of missed the big picture. It's also good to have an outlet of friends and family where you don't have to talk about science all the time.

Lauren: My dad has a PhD, and also studies parasites. So I didn't have to be the scientist of the family- my dad already had that covered. And it often seemed like he knew about everything, how things work in the world. And that can be intimidating to hear! Now that I have my PhD as well, I'm taking that role a little more with my family. My grandfather and my mom have actually attended some of my formal science talks at meetings, and it helps me think about how I communicate my work. I make sure at the meeting that my mom can understand my science presentation, because she's actually in the room. Among friends, if someone brings up raccoons I might talk about it. But we have lots of other interests in common- and I have non-scientist friends.

What do you like to do while you're not doing science?

Hung: I have too many hobbies! I'm starting to scale them down. I enjoy mushroom foraging, hiking, fishing, painting. It varies by day, and I'm pretty spontaneous.

Lauren: I'm building my hobbies back up, after I had scaled them down to finish my PhD. I'm feeling motivated to start running again. I play D&D and love that. I'm reading a lot of books and listening to podcasts. Puzzles can be calming. I also really enjoy spending time talking with small groups of friends.

When people approach you as an expert due to your science background, how do you respond?

Hung: I run a plant diagnostic lab, so this happens often with farmers. I start with a caveat that I don't always know the answers. I can guess what the disease is, but usually have to get a sample into the lab to confirm it. Often, it's not even a pathogen problem in plants, it's some kind of non-biological stress from over-babying the plants. Overwatering and too much salt can look a lot like pathogens to the untrained eye. Sometimes we get plants from the bonsai industry, where a $10k plant comes in sick. 30 years of careful cultivation, and the plant looks sick because the grower has spoiled it! People can get very worried about their plants, and will text and call me for updates. I also have to be careful in how I state my conclusions – based on what I found in the lab, here is what I'm confident to tell you. But you are always free to get a second opinion. 100% certainty is rare in science.

Lauren: There's a condition called "delusional parasitosis" in which people are convinced they have a parasite, despite all medical evidence. It's hard to tell someone that they are wrong about that. When I do outreach talks, sometimes people have strange ideas about parasites. I respond compassionately, but it's important to be clear about what makes biological sense. Sometimes friends assume that all humans have parasites. We all have lots of bacteria living within us, but they are not parasites. They are "commensal", meaning that the bacteria have no negative effect on us. Except when something really bad happens to your immune system, then the bacteria can overgrow and start to act like a pathogen, like a parasite. But you can't call these bacteria parasites of humans- because the vast majority of the time, they aren't! We're not riddled with worms or protozoans. There are parasites that are possible to get in the United States. But with sanitation and water filtration, we avoid most parasite threats. It's more of a problem in other parts of the world.

Why is science communication important to you?

Hung: The general public needs to be aware that plants do get disease, and where their food comes from. It affects us personally, and affects politics. If people know that some areas are still under active research- then when it's time to vote, people are more likely to really look into the issues, read about them, and come to a clear understanding. The plant disease clinic is a big outreach effort. We go to the farmers, to grower meetings. People need to know that science is not so complicated. Anyone can grasp a basic understanding of science! And if people realize that, they'll be more supportive of research.

Lauren: We need people to understand that science isn't so complicated. There are bits of science, some of the techniques, that are complex and difficult. But any scientist can talk to people about the basic ideas. I like to do outreach with a range of ages, from young kids up to adults. It's personally fulfilling and lots of fun. I really enjoy how easy it is to gross people out with parasites! It's funny to push those buttons just a little bit. I also like to break down the stereotypes, like the idea that someone who has a parasite infection is somehow "dirty". Parasites are super common in the world. About half of ALL organisms are parasites. It's also important that people realize when to be concerned about parasites. I also like just telling people about nematodes, which I study. Not all of those are parasites, but they are everywhere too.

Interview by Nicole Soltis of Science Says Photography by Bobby Castagna of Sac Science Distilled

Comments